Thought as Being

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

- …

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

Thought as Being

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

- …

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

Knowing the World and Knowing Thyself

How Humans Err in "Knowing the World and Knowing Thyself"

Limitations of Western Civilization’s Natural Sciences, Philosophy, and Psychology

A critique of reductionism, externalized cognition, and the disintegration of observer and observed

Human activities of understanding and transforming the world must be based on a correct understanding of the self.

However, we have a common habit: when everyone shares the same problem or lives with it for a long time, especially when the issue is hard to notice or cannot be solved, we often stop seeing it as a problem. Instead, we gradually get used to it, accept it, and unconsciously treat it as normal.

This issue also affects how we understand ourselves and our thought processes.

We have lived for a long time in the current low-level state of thinking without realizing its problems. So, we have to accept it as normal, and our subconscious does the same.

Almost everyone has this problem from early childhood. For example, when we are born, we start breathing immediately and keep breathing this way. Because everyone breathes like this, we think it is normal. But we rarely think about breathing, and understanding ourselves is even deeper than that.

In studying the "self," psychology and philosophy mostly use this same low-level state of thinking. What are the main mistakes that come from this?

First, there is the problem of studying the whole by examining only a part — that is, using the current low-level state of thinking to study other states of thinking. This approach relies not on empirical evidence, but on logical reasoning alone.

For example, philosophy points out that humans have an “instinct” — the instinct to pursue pleasure and happiness. But philosophy only treats this as an assumed instinct, something taken for granted. Because it does not use empirical methods, it cannot explain how this instinct arises, under what conditions it might disappear, or what its developmental process looks like. This fundamental issue remains unresolved. This is a clear case of using a part to try to understand the whole.

At the same time, since the current low-level state of thinking itself has problems, using this problematic thinking to study other thinking states means studying a problem by using a problem. This makes it impossible to reach correct conclusions.

Second, there is the error of using the content of thought to study thought itself, or using the research subject to study the research subject. To truly study the object of inquiry, we must adopt an objective stance — only then can genuine understanding arise.

These kinds of errors — partial perspectives, studying problems with problems, and studying subjects by subjects — are common in traditional psychology and philosophy’s investigations of thought. They ultimately prevent a true understanding of the self.

Integration of Disciplines

The world originates from a single root. So why are there so many different disciplines today? This is entirely caused by the derived states of thinking.

But since the root is unified, it is clear that all these disciplines will eventually return to the same point and share common laws. This may be what physicists pursue in the theory of a unified field.

If we deeply study the fundamental state of thinking and discover its laws, we can find the most fundamental laws of the world. Each discipline should be supported by these common fundamental laws. Once we find this root law, it can guide the development of all disciplines. In fact, the development of each discipline is merely an annotation and verification of this fundamental law.

Philosophy, as the discipline that studies the fundamental laws of the world's development, should lead the natural sciences. Unfortunately, it currently always falls behind natural sciences. Why is that?

It is because today's philosophical research does not grasp the root. Instead, it constantly studies trivial details. Moreover, philosophers tend to think from one particular state of thinking rather than first comprehensively and deeply studying their own thinking. They should study the world from various states of thinking, especially the fundamental state. Therefore, the philosophical theories produced are incomplete and unscientific and cannot effectively guide other disciplines.

—《Foundational Research on the Phenomenon of Thought》, Qingliang Yue

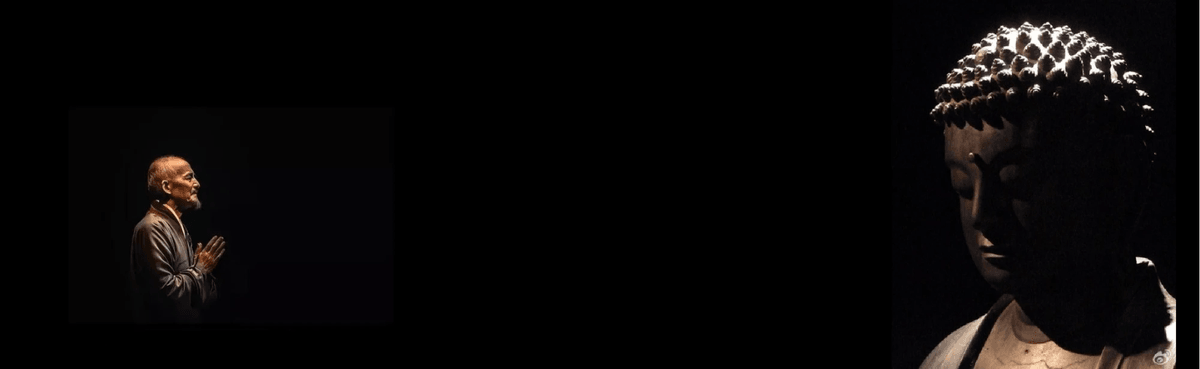

How Buddhism Knows Thyself

The study of the ontology of thought

self-knowledge through meditative insight, dependent origination, and the direct observation of thought's arising and cessation.

Buddhism’s study of thought is founded on rigorous empirical evidence, not on one or two isolated phenomena. In other words, Buddhist investigation into thinking is not based on mere logical reasoning but relies on extensive and strict empirical validation.

Through such rigorous empirical inquiry, Buddhism discovers that our thinking consists of two fundamental states: the fundamental state of thought, known as the Tathāgatagarbha (Buddha-nature) state, and the derived state of thought, which is the current deluded mind (klesha-mind) state. These two states together form the complete picture of "thought."

From this perspective, most people, being immersed in the current derived state of thinking, pursue empirical practices aimed at escaping this state to access other states—namely, the Tathāgatagarbha state. This often leads to a misunderstanding that the current state is inherently “bad.” However, fundamentally, the current derived state is also an expression of the Tathāgatagarbha in a broader sense. It is like the ocean and its waves: waves are part of the ocean, and when we define the ocean, we include the waves within it. This point is important to understand.

The derived state of thought can be further divided into a higher derived state and a lower derived state. The higher state corresponds to the general meditative (samadhi) state, while the lower state refers to the continuous, discursive thinking we experience daily.

In understanding these states of mind, people in society will recognize that the current thinking state derives from the higher state. This leads to two common insights:

- This thinking state necessarily carries traits of the higher state of mind.

- Since it evolved from the higher state and the fundamental state, it inevitably differs from them, and these differences cause many of the problems we encounter in daily life.

The Study of Thought Ontology and Buddhism’s Unique Perspective

The study of Thought Ontology focuses on investigating the structure of thought itself, and uses this understanding to address the problems that arise in thinking.

The structure of thought can be divided into three components:

- The ontology of thought (what thought is in its essence),

- The content of thought (what we think about), and

- The modes of thinking (how we think).

Philosophy and psychology mainly study the content of thought; cognitive science tends to study the modes of thinking. In contrast, Buddhism uniquely focuses on the ontology of thought.

It is essential to understand that true Buddhism is the study of the ontology of thought. Simply working with the content of thought—even reaching high levels of meditative skill—does not constitute Buddhism. Techniques for meditation existed even before Buddhism arose. Historically, many practitioners have concentrated on the content of thought. But to return to the Tathāgatagarbha (Buddha-nature), one must abide in the ontology of thought.

So, what is Buddhism?

To abide in the ontology of thought and return to the Tathāgatagarbha—that is Buddhism. Any practice focused on the content of thought, no matter how refined, is not Buddhism in the true sense. Psychology can also regulate mental states by engaging thought content, but it remains within the realm of conditioned experience.Those who have entered meditative absorption know that there is no essential difference between that state and our ordinary state—except for the shift in the content of thought. This means that as long as one abides in thought content, regardless of the depth of concentration or meditative achievement, it does not fundamentally belong to the Buddhist path.

Authentic Buddhism—the original and unaltered Dharma—is realized through abiding in the ontology of thought and returning to the Tathāgatagarbha. If we truly want to practice Buddhism, we must be clear about what Buddhism actually is. Without this understanding, one may think they are a Buddhist, while in essence they have not entered the true path.

—《Foundational Research on the Phenomenon of Thought》, Qingliang Yue

Theory of Conditionality,Methodology to Know Thyself and the World

Discover how all phenomena—mental and material—arise from conditions,

and how to trace back to the source through them

Origin and Multiplicity

The complex and diverse world originates from a single source. Under the influence of various conditions, this singular source continually evolves and gives rise to myriad forms. Through the study of the Theory of Conditionality, we aim to grasp the laws of this transformation—and, in doing so, uncover the method and path for returning to the source.

Layered Conditions and Fundamental Energy

Every phenomenon is formed through the layered accumulation of multiple conditions. Conversely, any such phenomenon can also be deconstructed—step by step—down to its root conditions. At the core of all existence lies a singular, original condition, which we refer to as fundamental energy.

Interwoven Conditions and the Whole

The conditions that shape our world are intricately interwoven, like the strands of a net. No single strand exists independently. This insight parallels principles in quantum mechanics, which emphasizes the inseparability of the object and its environment.

Our current state of thinking is also a conditioned structure. By analyzing its constituent conditions, we can trace it back to its original generative condition—what we call the fundamental state of thinking.

Compatibility and Conflict of Conditions

All phenomena arise from the compatibility of layered conditions. When a new condition is added and is compatible with the existing structure, a new phenomenon may emerge. When it is incompatible, it disrupts the existing structure, reducing it to a simpler, more fundamental state.

External causes do not destroy a phenomenon arbitrarily; they specifically dismantle the incompatible condition while leaving others intact.

Conditions and Temporal Process

Whatever is conditioned must undergo arising, transformation, and dissolution. Conversely, if a phenomenon exhibits birth, change, and cessation, it must be composed of conditions.

Thus, our current state of thinking also follows this conditioned process. ,we come to recognize the constituent conditions and evolutionary laws of our thinking—enabling us to engage various states of mind with greater clarity and precision.

The Nature of Reality

Conditioned phenomena are inherently insubstantial and lack autonomy. They change with their conditions and vanish when those conditions cease.

In contrast, that which is ultimately real exists independently, without relying on other conditions. It is the origin of all conditioned phenomena—autonomous and timeless.

Universal and Individual Conditions

All things coexisting within the same world share certain universal conditions, which allow them to coexist within a common domain. At the same time, each phenomenon has its own individual conditions, accounting for diversity and uniqueness.

It is the interaction between universal and individual conditions that produces both the stability and diversity of the world.

Conditions and Characteristics

Every phenomenon expresses its conditions through its observable characteristics. By studying these characteristics, we may infer the conditions from which they arise. Thus, characteristics become the key to uncovering the structure behind phenomena.

Simplicity and Reality

The simpler the structure of conditions, the more fundamental and autonomous the phenomenon. Simpler worlds are more free, more stable, and closer to the original source.

Simplicity yields freedom. The fewer the conditions that govern a phenomenon, the freer it becomes.

Simplicity yields lasting happiness. The fewer the conditions that give rise to joy, the more profound, enduring, and free that joy becomes. Artificial constructs add complexity, but complexity cannot bring true happiness.

—《Foundational Research on the Phenomenon of Thought》, Qingliang Yue

Mind-Matter Unity,Methodology to Know the Self and the World

Transcending dualism through contemplative realization:,

how the inner state of mind shapes the outer form of reality, and vice versa.

The Relationship Between Thought and Matter: Mind-Matter Unity

Matter is a relationship between the observer and the observed; there is no matter independent of consciousness, and no so-called objective matter existing separately. Matter is merely an illusion.

This illusion does not arise from nothing; it originates from a real entity that existed even before matter was generated and will never disappear. At most, it changes its form of existence. We call this true entity that generates all things the fundamental energy (or primordial energy).

Thought and fundamental energy are one and the same; we and the fundamental energy are one entity, two sides of the same coin—not a creator-created relationship, nor two independent things.

Thought possesses energetic attributes and material attributes; thought itself is the thinker.

Different material states of the same substance correspond strictly one-to-one with our different states of thought.

Different states of thought correspond to different material worlds, and we can freely maintain a mind-matter unity state with the material world corresponding to that state of thought.

Higher-level states of thought can maintain mind-matter unity with any lower-level matter, that is, we can use any lower-level matter as the body. The difference lies in the usage of different material states and functional states of that body.

In the fundamental state of thought, due to the absence of attachment and selective will, thought lacks the function of selection. The mind-matter relationship manifests as a universal unity with all material worlds.

In the higher states of the derived thinking state, especially during empirical validation of concepts like “no-self,” we can similarly maintain an integral mind-matter unity with all matter. However, this unity cannot be kept stable; once the selective function of thought returns, it will automatically be lost.

When we operate in the thought state corresponding to a certain matter, we maintain mind-matter unity with that matter. When we enter a thought state that does not correspond to that matter, we enter a state of mind-matter opposition with that matter.

In the derived state of thought, thought necessarily exercises selection and attachment. Different material worlds contain many different material bodies. We inevitably cling to a certain body as ourselves, maintaining a responsive thought state to that body and thus a mind-matter unity state. Consequently, we exist in mind-matter opposition with other material bodies. Therefore, mind-matter unity is the prerequisite for mind-matter opposition.

If we currently occupy a thought state inconsistent with our physical body, we will be unable to use or own that body. We will be in a mind-matter opposition state with this body and able to objectively observe it.

All material bodies in the same material world share common features as well as individual characteristics. If we are in a thought state corresponding to the individual characteristics of a particular material body, then we can maintain mind-matter unity with that body. If we are in a thought state corresponding to the common features shared by all material bodies in the world, then we maintain mind-matter unity with all matter in this world—that is to say, we can take the mountains, rivers, and land as our body.

—《Foundational Research on the Phenomenon of Thought》, Qingliang Yue

Experiential Verification,Methodology to Know Thyself and the World

A practical philosophy of cause and effect,

revealing the structure behind thought, world, and reality.

Fundamental Methodology of Ontology of Thought

The basic methodology of ontology of thought is empirical verification (practical proof), centered on the fundamental goal of returning to the fundamental state of thought and scientifically utilizing various states of thought.

The main methods involved are “mind observation,” “destruction,” and “correspondence.”

Ordinarily, most people dwell on certain thought objects or thought contents, actively engaging in or interfering with thought activities, rather than objectively observing the thought process itself.

Through the method of mind observation , we can objectively observe thinking activity and thereby reside in the ontology of thought itself.

Because the ontology of thought is also composed of conditions, when external factors destroy the constitutive conditions of the ontology of thought, we can return to the fundamental state of thought.

Correspondence means matching or resonating with the characteristics of other thought states, thereby entering those other states.

Destruction means breaking down the defining features of the current thought state, thus escaping from it. Each thought state is distinct because it possesses unique features that other states do not have. Conversely, to fully utilize a certain thought state, one must engage its unique features to remain within that state.

To return to the fundamental state of thought for the first time, one must use the method of destruction because we do not initially understand the fundamental state itself. By destroying the derivative thought states, only the fundamental state remains, allowing us to enter it.

The foundation of derivative thought states is attachment energy .

Therefore, only by removing this attachment energy can the derivative thought states be destroyed. To remove this attachment energy, one must reside in the ontology of thought, because the ontology of thought is formed by the combination of the fundamental state of thought and attachment energy.

Residing in the ontology of thought means residing in the attachment energy. Thus, a sudden external factor can break the attachment energy, destroy the basis of derivative thought states, and allow the return to the fundamental state.

Residing in the ontology of thought requires using the method of mind observation. Combining mind observation and destruction ultimately enables us to return to the fundamental state of thought.

Corresponding to destruction, these two methods—destruction and establishment—allow us to freely utilize various thought states.

Correspondence is about experience. If we only intellectually understand the features of other thought states without having any actual experience, then correspondence is impossible.

The characteristics running through all thought states are also present in our current state. We regularly experience these features and have rich experience in this regard. Therefore, we can use these valuable experiences to enter other thought states through correspondence.

—《Foundational Research on the Phenomenon of Thought》, Qingliang Yue

Know Thyself:Who Are You?

You are not your body,you are thought itself, boundless and pervasive.

To know yourself is to realize the unity of mind and matter

Who Are You?

Thought is the thinker itself; the present thought is you.

Your mind pervades everywhere. If you can think infinitely far, then the infinite far is you.

Wherever you can think, that place is also you. In other words, you exist everywhere. For example, if you now think of the next room, that next room is also you; you are there too. If you think of your hometown, your hometown is also you. But why can’t you see the next room or your hometown directly? This is due to the body—you are using the body as a tool.

The problem lies in the tool, not in you. If you no longer use the body as a tool, when you think of the next room, you immediately see it; when you think of your hometown, you see it instantly, without needing to travel by train. The train moves the body, but not the "you." You do not move; it is the tool (the body) that moves.

So, who are you? These two points show that thought is the thinker itself, and your mind is you.

This leads to a fundamental principle: the unity of mind and matter — mind and matter are one. This principle is detailed in our Basic Theory, which you can learn through study and verify through experiential practice.

What does the unity of mind and matter mean?

- First, thought has material attributes. Your mind possesses material properties. When you attain a certain level of realization, if you think of something—like conjuring an apple out of nowhere—you can manifest it immediately, much like the legendary Ji Gong. This means thought can manifest material forms.

Someone may ask: if only you see the apple, does it count as manifestation? No. Others must see it too; otherwise, it’s not a real manifestation. This relates essentially to the property of light, because everything is formed from light. When you master the state of light, you can utilize its function to manifest objects — this is the issue of “mind-generated body”. In Buddhist terms, this corresponds to the doctrine of “all phenomena are manifestations of consciousness”.

- Second, matter has mental attributes. All matter possesses mind-like qualities; in other words, all matter is “alive” but in different states. You, in your current state, can use your body but cannot use the table as a body because you haven’t entered the thought level corresponding to the table’s state—such as the states in the desire realm or meditative absorption . Others can, meaning matter possesses mental attributes.

This reflects the Buddhist teaching: sentient and insentient beings together realize Buddhahood . “Sentient” refers to your continuous, emotional, and reactive thinking . You believe only beings like yourself are alive, and objects like tables are not. This is a misunderstanding.

In Buddhism, “insentient” does not mean lifeless. Rather, sentience here means continuous emotional thought—the ongoing stream of likes, dislikes, anger, sadness, and so forth. Tables lack this emotional reactive stream; they have transcended it, existing at a higher state of life.

Thus, “sentient and insentient beings jointly realize Buddhahood” means those in the desire realm and those in meditative absorption (including tables and other matter) all eventually return to the Tathāgatagarbha and realize Buddhahood.

Understanding this requires recognizing that thought has material attributes and matter has mental attributes. This insight into sentient and insentient beings is a crucial aspect of self-recognition.

—《Foundational Research on the Phenomenon of Thought》, Qingliang Yue

More Study on Knowing the Self and Knowing the World

Registration

A Path of Cultivation and Realization through the Unity of Mind and Matter

About Us

Our Mission

We're Hiring!

A Path of Cultivation and Realization through the Unity of Mind and Matter

Subscribe of our latest