Thought as Being

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

- …

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

Thought as Being

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

- …

- Path to Essence

- Tree of Cultivation&Realization

- Scientific Med.Positivismvism

Natural Science and

the Unity of Mind and Matter

A meditative inquiry into physics, spacetime, and the cosmos—revealing the unity of thought and matter beyond the boundaries of Western science.

What is the origin of the world? What is the essence of the universe?

Who am I? Where do I come from?

These questions have long been the relentless pursuit not only of philosophers but also of natural scientists,mathematician, and they are of great concern to ordinary people as well.

The development of quantum mechanics has pointed a way forward for addressing these questions. Its study of the microscopic states of matter has fundamentally shaken the inherent notion of the reality and objectivity of matter. Quantum mechanics reveals that matter is a description of the relationship between the observer and the observed, thereby making the measurer an essential constituent of matter. Consciousness is thus involved in the formation of matter. Therefore, by deeply investigating consciousness — that is, thought — we can further unveil the secrets of matter and explore the origin of the world.

Ontology of thought is a multidisciplinary foundational discipline. Through a rigorous empirical system and countless repeatedly verified experimental results, ontology of thought asserts that the origin of the material world and the fundamental state of thought are one and the same; mind and matter are unified. Thus, we can fundamentally grasp the laws governing the material world through the study and mastery of thought.

Since the fundamental state of thought embodies the unity of mind and matter and constitutes the origin and essence of this world, the study of thought ontology becomes the foundation for other disciplines, which in turn become applied fields of ontology of thought. It is hoped that this discussion can provide a conceptual approach to natural science research, resolving some long-standing issues that trouble natural sciences. My research emphasizes using ontology of thought to interpret scientific experiments in natural sciences, focusing particularly on experimental aspects.

Experimentation forms the bedrock of scientific establishment; without experimental validation, no theory can truly become scientific. Similarly, every conclusion in ontology of thought is grounded in rigorous experimentation. Thus, the experimental results of ontology of thought are used to explain natural scientific experimental outcomes, interpreting the same phenomena — the essence and origin of the universe — from two complementary perspectives: matter and thought. In this way, a scientific system is formed to elucidate cognitive problems encountered in science.

It is believed that in the near future, natural science will achieve rapid advances under the guidance of ontology of thought. Conversely, the development of natural science will further promote the research, application, and popularization of ontology of thought in related fields.

The application of ontology of thought to natural science here involves using the principles of ontology of thought to explain concepts, conclusions, and experiments in natural science one by one. The first focus is on the speed of light, then on time, and the relationship between speed and time. What we study here is the speed of thought.

-Master Qingliangyue

Speed of Light

Quantum Mechanics

Time and Space

Universe

Thought Ontology Unlocks the Cognitive Limits of Natural Science

The first principle: thought is identical with the thinker; mind and matter are one.

This corrects a widespread misconception — that the body is the self, and thought is a mere function of the body. Under this view, matter is regarded as inherently real, while thought is seen as derivative. But in truth, what we perceive as matter is a kind of illusion. It is thought itself that is primary. Mind and matter are one.This point will be demonstrated from three perspectives:

- modern scientific explanation,

- philosophical inference,

- empirical verification within the framework of thought ontology.

The second feature of thought is its immense elasticity — infinitely expansive, infinitely contractive.

It can stretch outward without boundary — to encompass the entire cosmos — and inward beyond any discernible limit, contracting to dimensions smaller than any known particle. Thus, “its greatness admits nothing outside, and its minuteness admits nothing within.”In practical terms, we can contemplate the infinite vastness of the universe or the extreme smallness of subatomic particles — or even smaller, to the point of thought becoming ungraspable.

For clarity, we name the expansive mode of thought “surface-thought” and the contractive mode “point-thought.” These terms are provisional, introduced only for ease of discussion.The third feature of thought is the instability at the interface of thought states. This instability arises not only at the transition between ordinary states but also at the threshold between derivative and higher-order thought states.

At the boundary between two thought states, qualities of both coexist, rendering the interface unstable. In contrast, the states on either side of the interface are highly stable.

For example, once one is fully situated in the current thought state, that state is difficult to exit. Likewise, once absorbed into a state of Dhyana, one remains stable within it. Reverting from it also requires deliberate effort.The same is true of returning to the fundamental state of thought — the source of all thought — which is profoundly stable. Moving from this fundamental state back into the ordinary state is just as difficult.

Thus, the interface between two states is marked by instability, while both sides of that boundary are characterized by deep stability.Since mind and matter are one, the instability of thought interfaces manifests directly as the instability of matter itself.

Conversely, the stability of thought across a given domain translates into the stability of corresponding material states.This insight is particularly relevant to quantum mechanics.

Let us consider the transition from our current, lower-level thought state to a more advanced state. In doing so, one must pass through a transitional boundary — a zone we might call the “meditative absorption of the desire realm” (欲界定).

The inherent instability of this boundary expresses itself materially as the quantum uncertainty observed in microphysical phenomena.Quantum physicists attempt to observe subatomic particles through focused attention, yet their concentration lacks the purity of advanced contemplative absorption. They therefore rely on instruments, which reveal the material instability corresponding to their thought instability — because mind and matter are one.

When we return to the lower state of thought, the thought process is stable, and thus material reality appears stable. Similarly, if we move beyond the limits of conventional scientific thought — i.e., beyond the cognitive boundaries within which quantum mechanics currently operates — and ascend to higher derivative states such as Dhyana, the microphysical world again exhibits stability.

From the standpoint of thought ontology, then, the instability observed in quantum mechanics is not ultimate. It marks only a transitional interface. The true micro-world, rooted in the higher thought state of Dhyana, is stable — even governing the lower world from above.

All so-called miraculous transformations or “supernormal powers” take place in this higher domain.

For instance, in meditative absorption, when sages manifest phenomena in the mundane world — such as producing an object at will — the result is precise. One does not attempt to manifest a radish and accidentally produce an apple. There is no randomness, only stability.Once we cross the unstable interface and enter a higher thought state, stability is restored — both mentally and materially. This is the world of Dhyana.

The transition itself involves a flickering phase — as one moves from Stillness to Meditative absorption. Before the opening of the “heavenly eye” (天目), one experiences a threshold phase characterized by intermittent flashes — like the flicker of an old television screen. This visual instability arises because Stillness is being disrupted, while the new state of Dhyana is not yet stable. It is a liminal zone.

This explains the instability of both visual phenomena and quantum particle states observed during this process.

In meditative practice, one will encounter this flashing light stage — a perceptual precursor to deeper absorption. It is the tangible expression of the unstable interface between thought states.Why is it unstable? Because two incompatible qualities coexist: one state undermines the other. For example, Dhyana must be built upon Stillness. Yet the focused attention of Dhyana disrupts the tranquility of Stillness. Thus, attention remains unstable, and the thought state flickers — which is mirrored in the instability of material microstates.

Once one passes through this threshold, however, everything again becomes stable.

Due to the limitations of even the most advanced scientific instruments, current science remains bound to the present cognitive state — that of selective attention and conceptual focus.

If scientists cannot transcend this state, their research will remain confined to the transitional interface — incapable of surpassing quantum mechanics toward a higher scientific horizon.Therefore, to break through the current limits of science, one must resolve the problem of thought state itself.

Thought ontology offers the path of empirical verification to lead us into those higher states. Once scientists begin to engage in direct contemplative inquiry, adjusting their own state of thought, they will be able to investigate science from a higher cognitive vantage — and thus discover deeper layers of reality.

-Master Qingliangyue

The Speed of Light and the Supremacy of Thought

Ordinary people assume that the speed of light is the fastest in existence. Yet the speed of thought far surpasses it—not only in magnitude, but also in its remarkable freedom and controllability.、

This freedom manifests in thought’s capacity to accelerate or decelerate at will. Its controllability becomes evident through rigorous training, by which the movement of thought can be wholly governed. That is, one can freely enter any state of thought, return to the fundamental state of thought at will, abide in stillness, and enter meditative absorption as one chooses.

What must be achieved, then, is not merely the ability to exit from one’s current state of thought, but also the capacity to return. In any given thought-state, one should be able to enter, dwell, and withdraw freely. This is the mark of mastery: to no longer be a slave to thought, but to become its sovereign. Such mastery entails complete control over the dynamic processes of thought.

We have long assumed that the speed of light is the ultimate limit. In truth, the speed of thought transcends it by orders of magnitude. From this vantage, many phenomena commonly referred to as "supernatural"—such as seeing the future or the past—can be interpreted in light of relativistic principles. Once we accept the existence of states that exceed the speed of light, it follows naturally that such states permit access to time itself—to both past and future.

But why, then, do we not perceive these realities? This question lingers for many. The reason lies in the instrument of perception: we rely on the eyes to see, when we should be seeing through thought—through all states of thought. The eye is merely an optical device. Much of our scientific observation remains fettered by this visual apparatus. The vast array of scientific instruments we have built merely extend the reach of our sensory organs; they are auxiliary tools of perception. Yet these very sensory organs often become the chains that limit our vision of the world.

To truly observe the world in a scientific sense, we must abandon these perceptual crutches and instead perceive directly with thought—with the mind itself. Only through this direct experiential engagement can we attain a genuine understanding of reality.

-Master Qingliangyue

Quantum Mechanics

In the Microcosm, Particles Remain Indeterminate Prior to Observation, Existing in a Blurred Superposition of All Possibilities

This is because mind and matter are one. Before observation occurs, our thought remains in a macro-level surface state—that is, most people remain in such a diffuse, non-focused mode of awareness. Correspondingly, the material realm presents itself as a superposition of all possible states, undefined and indistinct. The particles, too, exist in an indeterminate condition. In this sense, the microcosmic world exists in a state of uncertainty. The consciousness within the micro-world and the objective world can no longer be separated—this is the very meaning of the oneness of mind and matter.

When Observed with Conscious Intent, Particles Manifest Determinacy

The crucial point here is “observed with conscious intent”—this is key. In general, when people observe the world, they do so passively and diffusely, operating in a surface-level state of thought. But when one observes with deliberate intent—when volition (cetanā) arises, and focused attention is applied—then the mind, which had once been expansively oriented toward the vast universe, now collapses inward to a single point of observation.

According to the principle of the unity of mind and matter, when the mind focuses with such intention, the corresponding material state also collapses into a definite micro-particle, manifesting a state of determinacy. Initially, the mind was unanchored, spread across a plane of indeterminate possibilities. Now, in focused observation, the mind locks onto a single point, and the material world reflects this by manifesting the particle aspect of matter with determinacy.

A Subtle Distinction: Determinacy of Form vs. Measurability

It must be noted, however, that while particles may appear in a determinate state, this does not imply complete measurability. Because micro-particles exist in the quantum realm, and because even focused attention is inherently unstable, the act of measurement remains subject to uncertainty. The micro-particle may be seen to manifest as a determinate state, yet the precision of its measurable attributes remains limited—this is the essence of the uncertainty principle, even under focused observation.

The Multidimensional World

Currently, scientists and mathematicians speculate about the existence of multidimensional worlds. From our perspective, the multidimensional world truly exists. We can even use certain methods to allow people to verify the multidimensional world and freely enter and exit these worlds.Within the multidimensional world, we mention a particular kind of world — the world of one person.

Scientists studying multidimensional worlds generally consider all worlds as common or shared worlds. However, in reality, there also exists a “one-person world,” which is reached through deep meditative absorption (dhyāna). A person who pursues stillness to an extreme can eventually enter this one-person world, where one can still see beautiful landscapes and rivers, but only that single person exists.

This differs somewhat from what ordinary scientists understand, so we briefly discuss this point.

Next, a classification of multidimensional worlds: multidimensional worlds can be classified according to states of thought, because mind and matter are unified. Under the same thought state, there correspond many material worlds, but these material worlds can be further subdivided.

Specifically, multidimensional worlds can be divided into “the world of meditative absorption (dhyāna)” and “ordinary scattered worlds.” The scattered worlds themselves branch into many worlds, and the meditative absorption worlds likewise contain many worlds. These different worlds share common characteristics but also have their individual particularities. The classification of these worlds is very complex and we will not delve into it here.

Now, regarding the intersecting compatibility of multidimensional worlds: why are multidimensional worlds mutually compatible and intersecting? It is because the world is a unity of mind and matter. Our thoughts possess this compatibility.

For example, now many people are thinking of the sky outside, the external world. Countless people are thinking simultaneously, yet their thoughts never obstruct one another, never cause traffic jams. Therefore, our thoughts have great compatibility, and so the material worlds also have great compatibility.

Where then are other worlds? Other worlds exist beside and inside your body and mine.

Using Buddhist terminology, where is the Pure Land? The Pure Land is right beside you, inside your body — it is not separate in space or time. So, we need to understand why multidimensional worlds are intersecting and compatible: this is because our thinking is in a holistic (plane-like) state. Everyone’s holistic thinking state is compatible and intersecting. Thought never experiences traffic jams or blockages, so the world cannot experience congestion either. Thus, multidimensional worlds stack layer upon layer, intersecting and compatible.

We cannot just sit on a spaceship flying to some place far away — there is no such thing as “far away.” There is no separation from the present moment.

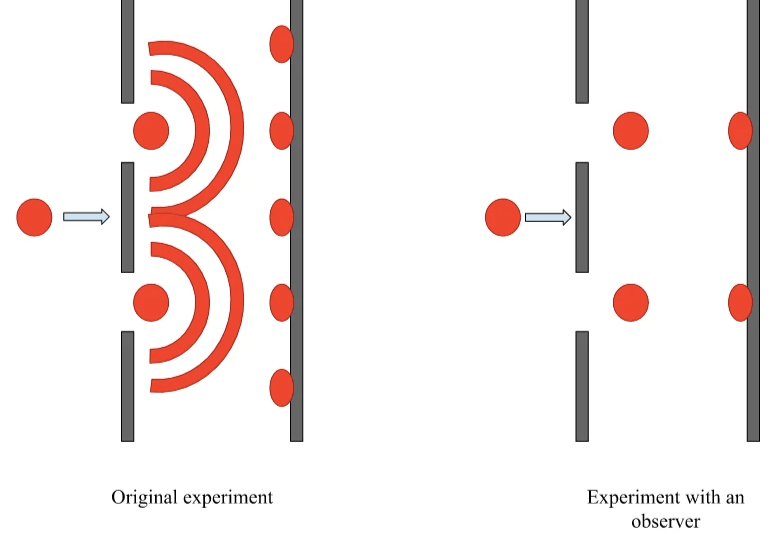

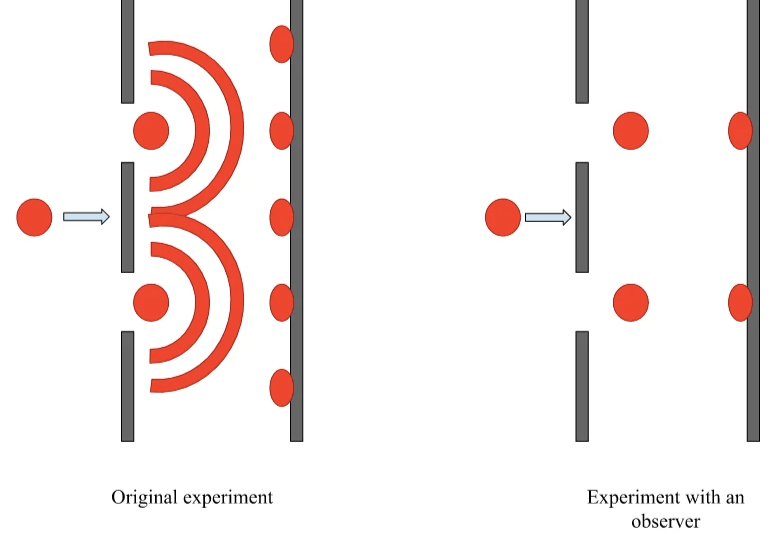

The Double-Slit Experiment

The double-slit experiment is a prime example of this phenomenon. Let’s discuss the entire process of the experiment.

At first, the observation is done using a beam of electrons to see whether matter behaves like a wave or a particle. Initially, the scientists observe the entire beam of electrons as a whole — in other words, they observe the collective behavior. At this point, naturally, the behavior shows a macroscopic, holistic (plane-like) thinking state, which manifests as a wave pattern.

Next, an instrument is set up to observe through which slit a single electron passes. That is, your attention shifts to individual electrons, watching how each electron behaves. This means your thinking transitions from a holistic (plane) state to a focused (point) state. At this moment, matter naturally presents itself as particles — the wave behavior disappears. When the observation instrument is removed and such focused observation stops, we return to the holistic thinking state, and the wave pattern reappears.

Now consider observing the electron just before it reaches the detection screen. Here, the act of observation again acts as a kind of hint or suggestion, implying that electrons are individually observed after passing through the screen. Because of this hint, the thinking state remains focused and point-like, meaning the particle state dominates and the wave state disappears.

Scientists often have the misconception that when you observe the electron in this way, it means the event of the electron beam passing through the double slit is already completed in a particle state. They think that the wave behavior collapses only when the electron is observed at the screen, and thus that the electron had to be a particle when it passed through the slits.

But in fact, this is not the case.

The speed of thought is extremely fast. When you observe the electron’s particle state just before the screen, your thinking rapidly shifts — because thought moves very quickly. This rapid shift causes the “hint” or focus on particle behavior to be projected backward onto the earlier part of the experiment, namely, the electron beam passing through the slits. In other words, your thinking’s state at the detection screen influences your conception of the electron’s state at the slits, retroactively imposing the particle state on the earlier moment.

This leads to the mistaken idea that the past can be determined only after the fact — that history is “decided” retroactively. Such a misunderstanding arises precisely because there is no knowledge of the ontology of thought and the study of thinking itself. People lack any concept of the speed of thought and regard thought as simply a mental idea, ignoring its material nature.

In reality, thought has material attributes, and matter has thinking attributes. Mind and matter are unified — they cannot be separated.

The Boundlessness of the Universe

The Limitation of the Fleshly Eye and the Transcendence of Thought

First, we must touch on the definition of the self: What is “I”?

In the common view, the self is the body, and thought is a function of the body. But for us, this is not the case—thought is the thinker itself.

That is to say, when asked “What is the self?”—undoubtedly, it is thought that is the self. The thought of the present moment is the you of the present moment; not the body, but the present thought is who you are.

Now, when we speak of science in relation to this, another concept comes into play: the unity of mind and matter. When discussing thought, we must understand the characteristics of thought—its tremendous elasticity.

This elasticity means: nothing is larger than thought, and nothing is smaller than thought.

What does it mean that “nothing is larger”? Close your eyes—imagine as vast as you like. As vast as your thought can be, that is how vast you are. Your body, your image, your entirety extends across the universe.

What does it mean that “nothing is smaller”? It means thought can contract to a state of absolute interiority, smaller than any particle.

Because mind and matter are one, when thought is in a vast state, it coincides with the boundlessness of the universe.

Thus, the reason we perceive the universe as boundless is because thought is boundless, and mind and matter are unified. The universe is ourselves.

Why then can we not see the edge of the universe?

We build spacecraft, optical instruments—still, the boundary remains unseen. In truth, we should be able to see it, because the universe is us. If the universe is the self, then the self should be able to perceive itself.

Why can’t we? Because we are using our eyes. The limitation lies with the eye.

The eye, as a physical optical device, cannot reach distant realms. Therefore, we must see with the mind.

Let us understand this: to see with thought is entirely possible.

A person who engages in spiritual realization will immediately understand this point. When we say to see with thought, it means to cast off the body, to transcend the body, to open the “divine eye.”

Now, do not imagine the divine eye to be yet another kind of eye. Do not be bound by form. The divine eye is not an actual eye—it does not “exist” in that sense. The divine eye is yourself—it is your present awareness. So do not mistake the divine eye as a physical organ. That would be a fundamental error.

The Nature of Cosmic Motion from the Perspective of Mind-Matter Unity

The expansion and contraction of the universe occur simultaneously. According to the principle of the unity of mind and matter, these are but the polar tendencies of thought.

One thought turns inward—this is contraction; the next thought turns outward—this is expansion.

One contracts, one expands—thus arises the apparent motion of the universe.

Light, Thought, and the Transcendence of Space-Time Cognition: From Relativity to Mind-Matter Logic

Light is the foundational concept in relativity; other concepts in the theory are built upon the constancy of the speed of light.

Here, light is regarded as one form of matter, corresponding to the derivative state of thought.

Light has a certain speed, but thought moves far faster.

Relativity suggests that as speed increases, time slows. At light speed, time halts—hence, concepts such as time reversal.

But thought surpasses the speed of light by far.Thus, thought can indeed perceive past and future.

Why don’t we see them? Again—because we are using the fleshly eye.

The eye is the obstruction.

The core idea remains: see with thought.

We cannot say this directly in social discourse—saying “see with the divine eye” will be dismissed as superstition. So we simply say: use thought to observe.

That way, the concept seems new and intriguing, and can spark interest.

Instability of Thought-State Interfaces and Their Relation to Quantum Mechanics

At the interface of two states of thought lies an unstable zone, for it simultaneously holds the characteristics of both states.These characteristics are often contradictory. Specifically, as we transition upward from our current state of thought, the state we seek is based on Stillness. Yet the act of focused attention—Dhyana—disrupts Stillness.

Thus, a kind of instability arises. This interface instability is essential to understand. It directly relates to quantum mechanics.

-Master Qingliangyue

Wormholes

In modern science, a wormhole is described as a tunnel connecting two distinct universes. According to the principle of the unity of mind and matter, the wormhole—as a manifestation of the material world—is intrinsically one with our thought. Therefore, by resolving the dynamics of thought, we can in turn resolve the question of the wormhole.

In other words, the journey between different worlds can occur either through the material realm or through states of thought. There are two pathways: one through the external world of matter, and one through the inner world of mind. Because mind and matter are one, both paths ultimately lead to the same destination. Thus, the method of generating wormholes lies in adjusting our thought-states to open such passages.

The formation of a wormhole often involves elements of chance. In scientific accounts, we encounter such phenomena in the form of objects that suddenly vanish or appear without warning—these are expressions of chance-triggered events.

But how do such chance factors operate? They momentarily shift one's thought into a particular state, and only through this state can one enter another state of mind—and thereby, another material world. That is to say, these chance events must bring the mind instantly into a specific condition. This is what we previously referred to as dhyana-strength or the power of meditative absorption. Crucially, such mental absorption is not cultivated through conventional training—it must be induced. Chance conditions can, in an instant, draw forth this depth of absorption.

In truth, all empirical realization (or verification) shares the same essential aim: to induce this power of meditative absorption.

Now, because such chance conditions may arise at any time or place, wormholes too may exist anywhere, at any moment. A wormhole forms in the very instant that the necessary conditions are met. These “conditions” are precisely those that induce a shift into a new state of thought.

But it is not necessary to passively await the emergence of chance events. Through the methods of Ontological Thought Studies, we can actively create the conditions for a wormhole. How, then, do we create a wormhole?

First, we must disengage from macro-level sensory experience. In other words, we must refrain from engaging with the gross perceptual world. How is this accomplished? By ceasing the function of the sensory faculties—for our experience of the world arises through the activity of the bodily sense organs. Thus, the first step is to prevent the senses from operating. In Buddhist terms, this is called the purification of the six sense faculties (liùgēn qīngjìng)—to completely shut down the six roots.

Second, we must break free from the continuous stream of associative thought. One may close the eyes and refrain from looking at the external world, yet still continue to imagine and conceptualize it internally. This, too, is a form of sensory engagement—not seeing, but "thinking in images." Therefore, we must remain vigilant at every moment to prevent the unfolding of continuous thought. A variety of methods may be employed to keep the mind from cascading into associative sequences.

When these two conditions are met, the wormhole arises naturally. At that moment, one enters another material world.

This approach provides a clear and applicable method for those in the natural sciences who may be intrigued by the idea of artificially generating a wormhole. While the notion may seem bizarre or fantastical, one can be taught this method directly. Should one earnestly practice it, they will indeed be able to generate a wormhole. They will open their celestial eye , behold the past and future, and witness the landscapes of other worlds.

-Master Qingliangyue

More on M&M unity and Nature Science

About Us

Our Mission

We're Hiring!

A Path of Cultivation and Realization through the Unity of Mind and Matter

Subscribe of our latest